New York State is often seen as completely developed at the end of the American Revolution. Its boundaries are portrayed as solidified, despite the fact that most of the state was still Native territory. This is a familiar story in the early national period as Americans envisioned the boundaries of the United States extending to the Pacific while Native groups west of the Appalachians held power on the ground. But New York State was unique in that it already was a state, even though half of the land was not yet incorporated. The story of the development and incorporation of western New York is not linear or inevitable. Native groups in western New York resisted state expansion well into the nineteenth century. Land speculators and surveyors laid out plans to incorporate what was imagined as western New York on a map into real state boundaries. These boundaries were to be solidified by the creation of townships, which would allow white settlers to buy land and create private property. Land surveyors drew the shape of New York as we know it today on survey maps, but these maps were often aspirational rather than reality. This conflict between the Holland Land Company and the Seneca over space and sovereignty shaped the landscape of western New York.

Prior to the American Revolution, land surveying and property allocation were often not carried out by land surveyors. Individuals would claim pieces of land that could be a variety of shapes based on natural boundaries, often leaving the less fertile land outside of their property lines. After the Revolution as the nation expanded in a systematic way, land surveyors became more important as they were responsible for expansion by creating new states, and in turn, new citizens. In western New York, this was carried out by the Holland Land Company who employed Joseph Ellicott as land surveyor and later resident agent. Although the systematic survey system had been used in the past all over the world, the township suddenly became the foundational building block of state formation in the United States. (William Wyckoff. The Developer’s Frontier: The Making of the Western New York Landscape. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 25.) Although land surveyors in western New York did not work for the federal or state government, their interests often overlapped as land surveyors profited from creating state boundaries.

The plans to incorporate western New York into the rest of the state required a complicated plan with many steps. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 is a well known case of how Native land was stolen in the early national period to facilitate white settlement. (Karim M. Tiro. The People of the Standing Stone: The Oneida Nation from the Revolution Through the Era of Removal. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), xiv.) Andrew Jackson used his executive power to expediently remove Native groups in the south to reservations in the west. But western New York was patently different from the rest of the country and the federal government did not have the authority to take land from the Seneca. Tracing back to seventeenth century land grants from the King of England, both Massachusetts and New York claimed that their territories extended all the way to the Pacific Ocean. To resolve this conflicting claim, in 1786 the two states came together at the Treaty of Hartford. The treaty included that the lands would become a part of New York as they were acquired from the Seneca, while Massachusetts obtained the pre-emption rights to the lands. The preemption rights allowed Massachusetts the first chance to buy the land when the Seneca agreed to sell. (Seneca Nation of New York. Memorial of the Seneca Indians to the President of the United States, Also an Address from the Committee of Friends, Who Have Extended Care to These Indians, and an Extract From the Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. (Baltimore: Printed by William Wooddy and Son, 1850), 3.) These rights prevented the federal government from directing land sales in western New York and the rights were bought and sold throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By the time the eighteenth century came to a close the Holland Land Company, a consortium of Dutch bankers, owned the rights. In 1797 after the Treaty of Big Tree extinguished Seneca title to all but 200,000 acres of land, the Holland Land Company spent an enormous amount of money and manpower on surveying and incorporating western New York. (William Chazanof, Joseph Ellicott and the Holland Land Company. (Syracuse: Syracuse Univeristy Press, 1970), 22.)

Joseph Ellicott was charged with surveying the almost four million acre territory beginning in 1797. The survey took two years and required the employment of 150 men. Ellicott’s undertaking was named the “Great Survey” and included adjusting the boundaries of the Seneca reservations during the survey that had been agreed upon at the negotiations at Big Tree. (Brian Phillips Murphy. Building the Empire State: Political Economy in the Early Republic. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 166-177.) Although the Holland Land Company had no authority to be present at the Big Tree negotiations, because they already invested money in land speculation in western New York, the company gave money to both the interpreters and the federal agent present at the treaty to ensure that the Seneca were left with only 200,000 acres. (Chazanof, 22.) The Holland Land Company’s bribe of the federal commissioner at Big Tree directly violated the Trade and Intercourse Act of 1790, which gave the federal government sole authority to deal with Native groups. (“An Act to Regulate Trade and Intercourse With the Indian Tribes, July 22, 1790.” http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/na024.asp) The Treaty of Big Tree in 1797 was the result of illegal private interests, violating federal law in order to extinguish Seneca title to land west of the Genessee River.

The process of surveying land across the United States was made complicated by the existence of Native reservations. Later nineteenth and early twentieth century federal policy to move reservations farther and farther west and eventually encourage Native groups to move off of reservations altogether shows how complicated the process of westward expansion truly was. This was especially true of the Seneca reservations in New York at the end of the eighteenth century. Not only were the reservations not in the same square grid as the townships, but the Treaty of Big Tree included that Ellicott consult the Seneca on the exact boundaries of their reservations. (Chazanof, 24.) Incorporation was again complicated because the Holland Land Company ran into issues when trying to distribute these parcels beginning in 1801. Ellicott wanted to play a larger role in distributing the individual parcels, but he misjudged the interest in lands in western New York from season to season. Parcels were sold unevenly rather than across the grid and not as quickly as the company anticipated. (Wyckoff, 119.)

Holland Company officials blamed Ellicott for selling to “pioneers” who did not turn into proper settlers quickly enough. Rather than settling down and farming the land, the individuals who purchased from Ellicott extracted marketable resources, like timber, from their parcels. By the 1820s, the Holland Land Company was over four million dollars in debt and Joseph Ellicott was fired. (Charles E. Brooks. Frontier Settlement and Market Revolution: The Holland Land Purchase. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 84.) The rhetoric surrounding Seneca land claims and attempted removal is baffling considering the uneven and chaotic nature of land settlement in western New York. The argument used to convince the Seneca to give up their land, the same argument which formed the basis of Manifest Destiny, was that white populations would overrun Native groups. White population pressures would compel or force Natives to give their land to the United States. This was rarely the case. A comparison of the white population and Seneca reservation boundaries shows that land company officials falsely argued that white population pressures in western New York would overrun the Seneca.

This project explores the “Great Survey” of 1797-1799 utilizing census data and georeferenced surveys of intended and actual land cessions. By examining the relationship between white population pressures and the contestation of reservation boundaries using maps created by the Holland Land Company, and by reading between land company aspirations and the actual outcomes of treaties and land cessions, it is clear that Native actions shaped the physical landscape of western New York. The Seneca, the state and federal governments, the land companies, and white settlers grappled with and understood sovereignty and space-making in very different ways. The use of maps created by the Holland Land Company as aspirational rather than documentary show how the changing landscape in western New York was altered by intersecting and conflicting sovereignties.

The maps used for this project are from the archives of the Holland Land Company and were digitized by the Archives and Special Collections of the Daniel A. Reed Library at SUNY Fredonia. Most of the maps were created by Joseph Ellicott, but for many of the maps it is unclear exactly who created them. It is likely that other surveyors employed by the Holland Land Company also created some of the maps used for this project. I created graphs that compare acreage of each reservation between 1799 and 1829 and white population by county between 1790 and 1820. More questions are raised about why the Holland Land Company believed they could pressure the Seneca into selling their lands when the population census data and reservation acreage data are placed side by side in a line graph.

In the line graph with only two lines, comparing acres with population, the reservation acres are represented by the blue line, while the populations of the counties in western New York are represented by the orange line. The line graph shows that although government and land company officials believed Seneca land would easily be acquired through treaty negotiations, the Seneca did not give up a significant portion of land between 1790 and 1829. The acreage decreased slightly in 1800, but increased steadily to 1829. There is no treaty associated with 1800, which indicates that the 1800 map was likely a possibility for reservation boundaries during the Great Survey. There was a decrease again in reservation acres in 1802 to 18,829, although again there was no treaty associated with this date. The decrease in reservation acres in both 1800 and 1802 points to the possibility that land surveyors envisioned a decrease in reservation acres after the Great Survey. If this is so the maps drawn in 1800 and 1802 were likely aspirational on the part of the land surveyors.

In 1790, reservation acres were measured at 21,210 while the white population of all of the counties in western New York was 1,074. By 1829, the reservations were at 20,782 acres while the twelve counties in western New York had a white population of 273,195. It is clear that the Seneca did not lose very many acres between 1800 and 1829, even though the white population grew slowly between 1790 and 1800 and then quickly between 1800 and 1829. Despite the argument that the Seneca would be pushed off their land by white settlers in the 1790s, the graphs show that the increase in the white population did not compel the Seneca to sell land during this period, perhaps revealing that the Seneca did not see their white neighbors as a threat before 1829.

The census data indicates that there was no white population in the western most portion of New York in 1790. Although this may not be entirely accurate as 1790 was the first federal census and western New York was not yet surveyed as formally incorporated into the state, it is likely that the white population was not very high. Transcripts from treaty negotiations throughout the 1790s and into the nineteenth century show that negotiators for the land companies and federal government tried to convince the Seneca that pressure from their white neighbor population was a reason they should give up their land. (Red Jacket. “The Treaty of Canandaigua, 1794” in The Collected Speeches of Sagoyewatha, or Red Jacket, ed. Granville Ganter (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 66; Red Jacket “The Treaty of Big Tree” in The Collected Speeches of Sagoyewatha, or Red Jacket, ed. Granville Ganter (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 91.) At the Treaty of Big Tree in 1797, Thomas Morris, who held the treaty negotiations to extinguish Seneca title in order to sell to the Holland Land Company, argued that the Seneca were already surrounded by their white neighbors. (Ganter. The Collected Speeches of Sagoyewatha, or Red Jacket, 86.) But the census data does not indicate a heavy white population living in the region where most of the Seneca reservations were. Red Jacket, a Seneca leader, counter argued that the Seneca would be overrun by white neighbors only if they gave up more land. (Red Jacket. “The Treaty of Big Tree” in The Collected Speeches of Sagoyewatha, or Red Jacket, ed. Granville Ganter (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 91.) Seneca arguments for remaining on their land focused more on the fact that the Seneca were a sovereign nation, not on the white population.

While it is possible that the white population increased between 1790 and the Great Survey in the late 1790s, the prediction by land company officials of an influx of white settlers in the area appears to be aspirational rather than what was happening on the ground. Even by the 1800 census, the two counties that made up western New York were very lightly populated. Like the rest the United States throughout the nineteenth century, many American leaders believed the land would be filled evenly and rapidly as Americans expanded westward under Manifest Destiny. But in western New York, as Joseph Ellicott’s failures to rapidly settle the land show, these white treaty negotiators used exaggerated information to persuade the Seneca to give up portions of their land. Although the 1799 map and earlier maps in the collection show the western most portion of New York State as fully incorporated into the rest of the state as we see on maps today, this was clearly not the case in terms of political control and citizen population.

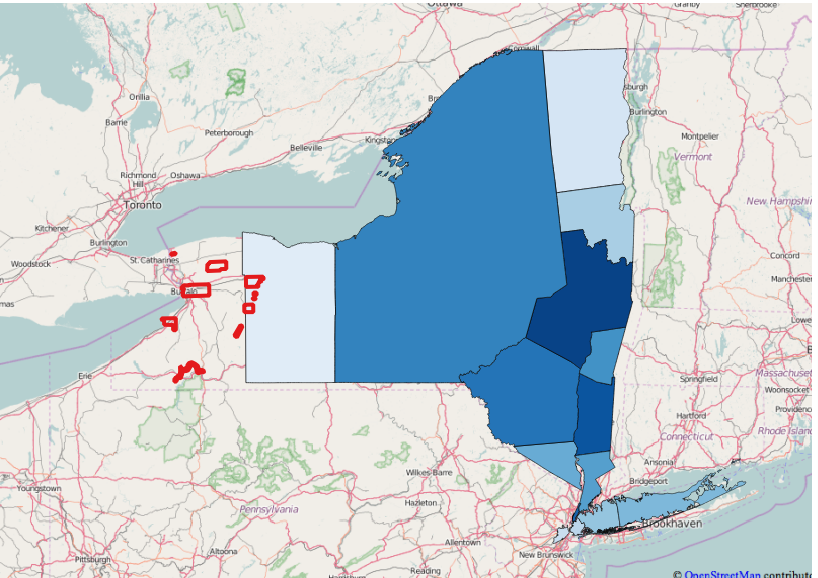

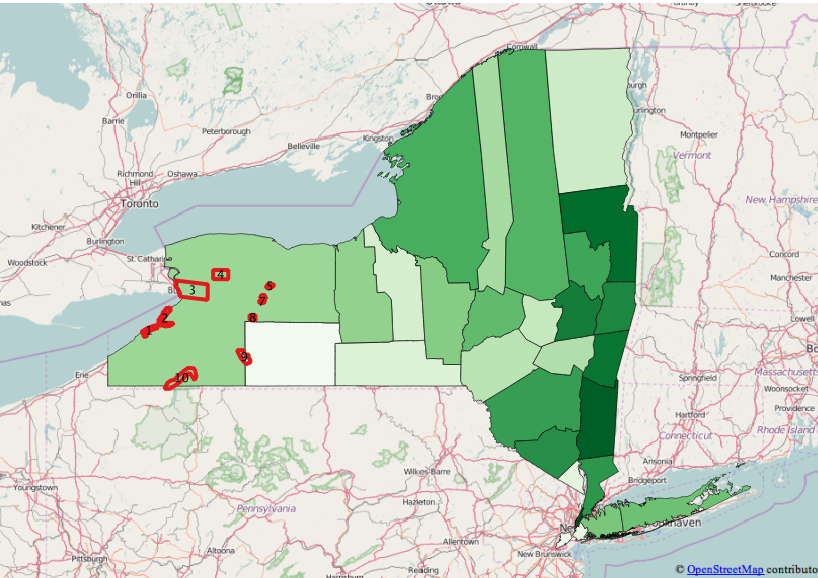

This false sense of incorporation became more clear after I layered and georeferenced the Holland Land Company maps. I outlined the reservation boundaries for each map and calculated the acreage of each reservation for each year and added the modern reservation boundaries. I added county boundaries and census data from the years 1790, 1800, 1810, and 1820. This allowed me to look at the shift and growth in county boundaries over time and how they overlapped with reservation boundaries. The first visualization using QGIS shows the 1790 white populations divided by county with the reservations from 1799 layered over the counties. While white population growth in Ontario county, the western most county in New York, is very likely in this nine year period, it is unlikely that the white population grew to a size that would put pressure on the Seneca to relocate, as the “Great Survey” was still taking place in 1799. This space had not been completely bounded and divided by the Holland Land Company and Joseph Ellicott had not yet begun his efforts to promote white settlement.

The second visualization using QGIS shows that by 1800, Ontario county was divided into Ontario and Steuben counties, but white population was still very light compared to counties in eastern New York. These maps comparing white population with reservation boundaries show again that while U.S. Commissioners throughout the 1790s made the argument that the Seneca would be compelled to sell their lands as pressure from white neighbors increased, the white population in western New York was not large enough to warrant any actual threat to Seneca land possessions. Federal and land company officials used false information to try to force the Seneca to give up land, as these officials legally had nothing else to bargain with. The preemption clause allowed for the Seneca to sell land only when they chose to sell land. If the land company wanted to acquire more land from the Seneca, they would have to do so illegally, as they often did into the nineteenth century.

One inconsistency is revealed in the map layers themselves. On the map created by the Holland Land Company in 1800, the Cattaraugus Reservation is shown as two pieces, while on every other map used in this project, it is drawn as one reservation with a consistent shape. Because this map was drawn at approximately the same time the Great Survey was wrapping up, it is plausible that the shapes shown on the 1800 map were a possibility for the resurveying of the Cattaraugus reservation based on Seneca demands, as the Treaty of Big Tree in 1797 stipulated that the Seneca had to work with Ellicott to determine their exact reservation boundaries. The Cattaraugus reservation on other maps borders Lake Erie, but takes up very little shore line. But the map in 1810 shows Cattaraugus bordering a much larger portion of the lake. There is documentation for Ellicott surveying the Buffalo Creek reservation away from the shore of Lake Erie in 1798. He knew the importance of controlling the land along Lake Erie and excluded that portion of the lake shore from the Buffalo Creek reservation in his survey. Ellicott called the shore “one of the Keys to the Companies land.” (Chazanof, 26.) This could also be the case with the Cattaraugus reservation as it would be logical that the Seneca would want to control more shore line of Lake Erie. Alternately, Cattaraugus as drawn in 1810 looks as though the surveyor was trying to push the land flat against the western most edge of New York State so as to separate Seneca lands more clearly from the surveyed townships. It is possible that an explanation for this inconsistency exists in the field notes of the survey.

In the visualization showing the percent change in reservation acres over time, there was a 75% increase in the acres of the Cattaraugus reservation from 1799 to 1800, showing that Cattaraugus when divided into the two shapes was much larger than when in one piece. But by the map drawn in 1802 there was a 31.2% decrease in the amount of acres when Cattaraugus was depicted as one piece again. The increase in the percentage complicates this story further, as it would not make sense for a land surveyor to increase the acres of the Cattaraugus reservation by such a large percentage if it were the goal of the company to reduce Seneca land claims. This inconsistency again will require further research into the field notes of the Holland Land Company archive.

Together, these visualizations show that despite the Holland Land Company’s belief that they would quickly make a lot of money from selling Seneca lands, acquiring Seneca territory was not as easy as they thought. Even with the acquisition of the title, the Holland Land Company could not predict how many people would move to western New York, their settlement patterns once they arrived, or how settlers would use the land once it was sold. Despite arguments made by the land company, the state, and the federal government about inevitable white population pressures as an early form of Manifest Destiny, Seneca landholding remained steady in the early nineteenth century as they resisted pressure from the land company to give up their territory.

Bibliography

Primary and Secondary Sources

“An Act to Regulate Trade and Intercourse With the Indian Tribes, July 22, 1790.” http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/na024.asp

Brooks, Charles E. Frontier Settlement and Market Revolution: The Holland Land Purchase. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996.

Chazanof, William. Joseph Ellicott and the Holland Land Company. Syracuse: Syracuse Univeristy Press, 1970.

Ganter, Granville. The Collected Speeches of Sagoyewatha, or Red Jacket. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006.

Murphy, Brian Phillips. Building the Empire State: Political Economy in the Early Republic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Seneca Nation of New York. Memorial of the Seneca Indians to the President of the United States, Also an Address from the Committee of Friends, Who Have Extended Care to These Indians, and an Extract From the Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Baltimore: Printed by William Wooddy and Son, 1850.

Tiro, Karim. The People of the Standing Stone: The Oneida Nation from the Revolution through the Era of Removal. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011.

Wycoff, William. The Developer’s Frontier: The Making of the Western New York Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

Maps

“Genesee Lands with Tracts Granted by Robert Morris to HLC; 1799? :: SUNY Fredonia.” Accessed February 13, 2016. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/XFM001/id/497/rec/164.

“Land Possessed by HLC in New York and Pennsylvania; 1800? :: SUNY Fredonia.” Accessed February 13, 2016. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/XFM001/id/347/rec/171.

“Map of the Genesee Territory with Roads, Counties and Towns: 1802 :: SUNY Fredonia.” Accessed February 2, 2016. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/XFM001/id/360/rec/210.

“Map of Genesee Accompanying the Account of 1812 :: SUNY Fredonia.” Accessed February 2, 2016. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/XFM001/id/495/rec/316.

“Map of Genesee with Townships in Counties & Inhabitants; 1814? :: SUNY Fredonia.” Accessed February 2, 2016. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/XFM001/id/379/rec/331.

“Map of the Western Part of the State of New York Including the Holland Purchase, Exhibiting Its Division into Counties and Towns :: SUNY Fredonia.” Accessed February 13, 2016. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/XFM001/id/957/rec/544.

“Map of Tracts H, M, O, P, Q, W, the Indian Resevations & Roads; 1829 :: SUNY Fredonia.” Accessed January 31, 2016. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/XFM001/id/193/rec/76.